Happy New Year! Hope you all had a lovely holiday season.

We’ve put together our writing contest schedule for 2026.

CommuterLit has four writing contests per year. Simultaneous submissions, submissions of reprints (stories or poems previously published in print or online) and multiple submissions are welcome. The top five submissions in each contest are posted on CommuterLit and receive cash prizes:

First-place: CA$100

Second-place: CA$50

(3) Honourable Mentions: CA$25

Entry fee: CA$4

Valentines Week 2026 — SUBMISSION WINDOW OPENS NEXT WEEK! Love Stories (max. word count of 2,500). Submission window: Jan. 12-26, 2026. Winning entries will appear on CommuterLit the week of Feb. 9-13, 2026.

Poetry Week 2026 — Poem or series of poems (max. word count 1000). Submission window: April 13 – 27, 2026. Winning entries will be posted the week of May 11-15, 2026.

Flash Fiction Week 2026 — Flash Fiction stories (max. word count 500). Submission window: May 19 – June 1, 2026. Winners will be posted the week of June 15-19, 2026.

Halloween Week 2026 — Scary Stories (max. word count of 2,500). Submission window: Sept. 21-Oct. 12, 2026. Winning entries will be posted the week of Oct. 26-Oct. 30, 2026.

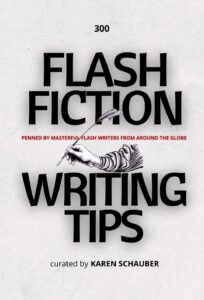

New Listing on our Book Store page

Any flash fiction writers out there? You might be interested in this new non-fiction book curated by CL contributor Karen Schauber. Go to the Book Store page and scroll down to Non-fiction.